Crime and Punishment in Ancient Egypt

Before talking about crime and punishment in ancient Egypt in terms of legislation enacted by the ancient Egyptian and about litigation procedures and members of the court and the penalties that were imposed on the offender, such as corporal punishments such as death, beating and flogging, as well as penalties restricting freedoms such as imprisonment and exile, the names and concept of punishments in ancient Egypt, and the teachings of Ptahhotep For children and the laws of Horemheb regulating social life in ancient Egypt, we must first set a model for a trial to learn about crimes and punishments, the powers of judges, seriousness and concern for justice.

The trial that we have before us is the trial of King Ra Messis III (dynasty 20). The choice of this trial is because it is the most accurate, detailed and clear trial that has come to us.

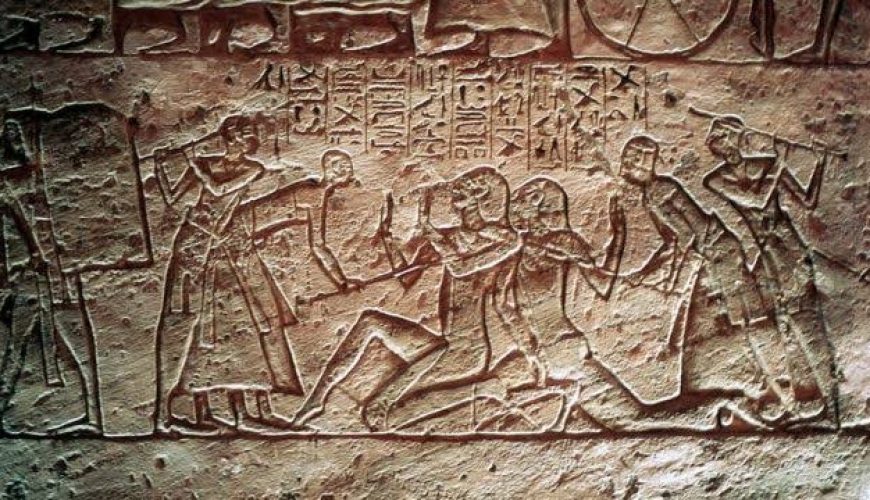

King Ra Messis III was one of the greatest kings of Egypt at the time. Still, unrest and demonstrations spread throughout the country at the end of his life, and his wife (Queen T) took advantage of these disturbances. She agreed with some traitors from the royal court, women and senior officials to kill the king and appoint her son (Pentaur) king of Egypt. The plan was executed tightly, and the king was actually killed. Soon the conspiracy was discovered, and the civil trial was formed and began to arrest the perpetrators and collect irrefutable evidence of the commission of the crime. This is according to what was mentioned in the Turin Judicial Papyrus. The trial was formed of 14 judges at first, but on a suspicious night, 3 He spent them secretly to spend a night in the house of one of the accused, where there were the accused women. These judges quickly moved from the court bench to the dock with the accused, and two of them were sentenced to (nose cut), and the latter was acquitted, and one of the judges committed suicide after hearing the verdict and before the sentence was executed.

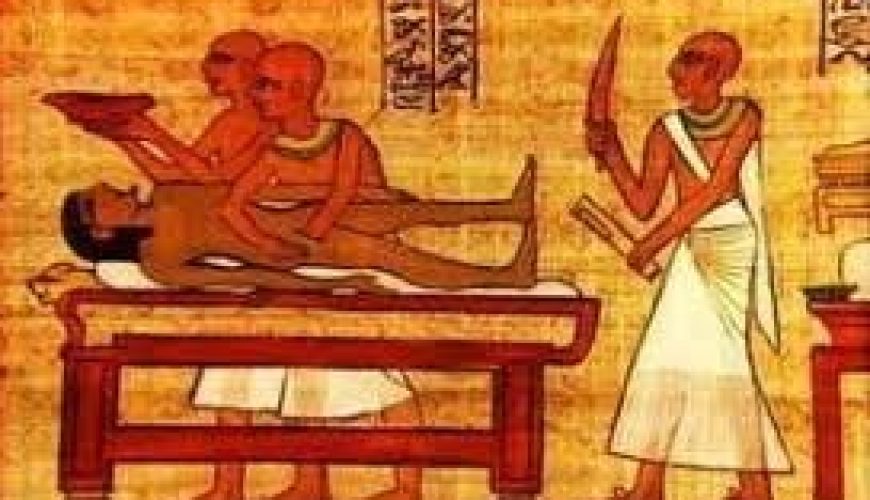

While completing the consideration of the case, the remaining judges discovered that there was a theological aspect in the case, as it was proven that the defendants used magic through their ages in the royal palace library on a recipe that instructed them to make wax statues that they made in the form of guards and recited their magic and spells on them, to seduce their owners and weaken their resolve. Or so the conspirators hoped.

Because magic was forbidden, the court ruled that there was no jurisdiction, and the case was transferred to the theological court.

The theological court received the order, and all the details of the plot were revealed. The court sentenced the defendants to be different and different sentences, each according to the type of his participation in this crime, including the Queen and the Crown Prince (Pentaur). From that case, we conclude the following:

• The diversity of judicial systems from civilian to theological may be equivalent to what we know today of civil and military justice.

• No one was above the law, not far from punishment and deterrence, even if he was a judge, a queen or the crown prince.

• The punishments, despite their diversity, were not excessive in cruelty but were relatively merciful. Only a few were executed, and the rest were either punished by banishment, cut off the nose, deafening the ear, or flogging.

• The judiciary was aware of the various precise jurisdictions and the importance of transferring cases to the competent courts.

• The issue of using magic is in the widespread perception that only the heavenly religions criminalized it. As for it being a crime in ancient Egyptian law, this is a surprising thing that calls for contemplation and deserves research.

And if we want to talk about some of the legislation enacted by the ancient Egyptians, we will not find better legislation and laws (Hoor Moheb), this man who was not of royal origin as Egypt knew, but with his wisdom and was able to rule Egypt and married the noble (Mutt Najmat) who is of royal blood.

These legislations, which were inscribed on the inner face of the tenth edifice at Karnak, emphasized in their preamble that he regretted the loss of authority in the land and that he wanted by enacting those laws to establish justice and eliminate acts of looting and violence and that he dictated them himself to the people of his court and that he chose judges who were distinguished by high morals and integrity, who were aware of the mysteries of matters and who were familiar with the relationship between the ruler and the ruled.

We mention very briefly some of those laws and legislation that he enacted (Hoor Moheb):

• Cut the nose for anyone who hampers a ship carrying taxes to the state coffers or taxes loaded to the king.

• Anyone who tampers with state officials and inflicts injustice on the peasants by taking some or all of their crops illegally in the name of the king shall be punished.

• Imposing heavy control on tax collectors to prevent them from exploiting their influence in the face of injustice.

• Punishing those who practice cruelty and excessive work on slaves who are foreign prisoners of war.

• The bottom line in the laws of (Hoor Moheb) that the poor man is the intended goal of protection from injustice, bribery, administrative corruption, and social prosperity is the goal he seeks through his legislation.

• Possession of stolen goods or resisting state officials are considered criminal charges. In contrast, cemetery robbery is considered the worst, and the crime of non-fulfilment of debt is considered very serious. Perpetrators are often sentenced to return the amount owed with a high interest rate.

In general and a comprehensive view of the dynastic period, we see that concerning the legal system, Maat represented the basic law for all social classes in contrast to the injustice and barbarism that was called (Asphalt). Maat represented the ancients justice, truth, cosmic order and good morals, thus taking its famous feather in court. The Hereafter is a distinguished centre. The feather of truth (Maat) is placed in a pan against the weight of the heart of the dead to know what the dead did in this world of a righteous, normal, and straight life.

There was no one above the law in most families, and the citizens of ancient Egypt were obedient and subject to the law, as they feared punishment in this life and the hereafter, as we see this in the so-called (Book of the Dead). seen by the king as the supreme judge.

Even in some schools of ancient Egypt, we find the most famous teachers and educators teaching students some of those principles and principles.

Comment (0)